Despite what some people will persistently argue, literature is not objective. I come to this conclusion after reflecting on two important ideas: (1) that the so-called “great” Literature is purely a social construct, and (2) literature is not based on what is written but how one interprets it.

Allow me to begin my discussion with the social construct that is “the literary canon.” There is no such thing as “great literature.” It simply does not exist. This unquestioned canon “has to be recognized as a construct, fashioned by particular people for particular reasons at a certain time” (10). Let’s not forget that art is often merely a commodity, just like most other things in life. Some of the most esteemed writers wrote purely to influence or persuade people politically, economically, or socially. These types of writings became valuable because they materialized the visions of upper-class, white society. Because of this, the “value” factor becomes problematic. “Value,” after all, “is a transitive term: it means whatever is valued by certain people in specific situations, according to particular criteria” (10). Therefore, literature is not objective. Instead, it is a subjective construct based on the decisions of only a few men. Since this is the case, “it is thus quite possible that, given a deep enough transformation of our history, we may in the future produce a society which is unable to get anything at all of Shakespeare,” who is, of course, part of this biased canon.

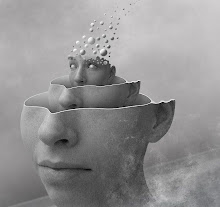

All this brings me to point number two: Literature is not based on what is written but how one interprets it. Let me illustrate with an example.

First, let’s consider this photo:

At first glance, this may seem to be a very basic picture pointing to an exit from a subway station. However, let’s imagine this scenario: a woman who has been oppressed her entire life decides to run away. She might view the subway station as a representation of her life – the timely schedule the subway runs on could be compared to the strict routine of her life, while the narrow walls may represent the limited chances for escape from such a mundane existence. For her, then, the “way out” sign could be symbolic and meaningful in ways other people cannot fathom. It could symbolize her chance to escape and free herself from the firm grasp of societal expectations.

The “way out” sign, then, can have multiple interpretations based on context and personal experiences. In the same way, literature – including any form of art – is not based on what is written literally, but how one interprets its meaning. The interpretation is more important than the text itself.

Literature, like all forms of art, is subjective. It receives its value not because a few white men chose to label it “great” decades ago, but because it has meaning to someone somewhere.

Works Cited:

Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory: An Introduction. 2nd ed. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 1996. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment